An Angel Serves a Small Breakfast

Paul Klee (German, 1879-1940)

Lithograph with additional watercolors,1920

Metaphysics

For a while after he died

my father didn't seem to

discern dream visitors, but

I was amazed nonetheless

to witness his swift and

serene rejuvenation. From

time to time I'd find him

dining outdoors in beautiful

locales, a multicolored

grain on his plate I'd

never seen elsewhere.

Yes, laughed the server,

It's a staple here; a sort

of national dish, I guess,

like potatoes in Ireland,

pasta in Italy, cous cous

in Morocco, rice in Japan

or Madagascar. We can't

get enough of it, and it's

remarkably nutritious.

What's it's called? I asked.

She replied, metaphysics.

Poetry

November 2015

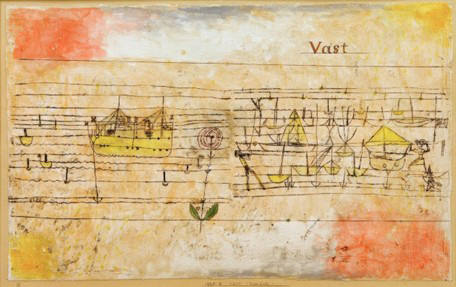

Melody and Rhythms

Paul Klee, German (1879-1940)

Watercolor, 1925

Philosophical Sonata

I was notified in a dream that my solitary studies—of which few knew and nothing much had ever come—had earned me an honorary degree in a little-known branch of philosophy. The degree would be conferred at a nearby university on such-and-such a date. They hoped I could be present .

Arriving at the ceremony on the appointed evening, I found my mother, much to my surprise, already onstage, seated at the piano. She announced that, in lieu of a speech in my honor, she would perform her rendition of a book I loved, a volume that was the heart and soul of my studies. As she began to play, I was amazed that a book, any book, could function as a musical score. But even more astonished that the long, arduous, mysterious opus that had come to mean so much to me—a hundred books in one, a lifetime of grappling—was so lucidly expressed by the wondrous sonata my mother played that night.

After the applause abated, she laughingly told the audience that she’d learned to play the book simply by dying. Whereas for her daughter (and here she gestured toward me), it was a lifelong métier ...

It then hit me that this was the answer I’d been waiting for. Nothing on the order of, say, Martha Argerich performing Rachmaninov at Lugano. No, this would be something else entirely. In taking the stage, I thanked our hosts for organizing this extraordinary occasion—then sat down at the piano and began to play.

The Manhattan Review

Fall/Winter 2022/23

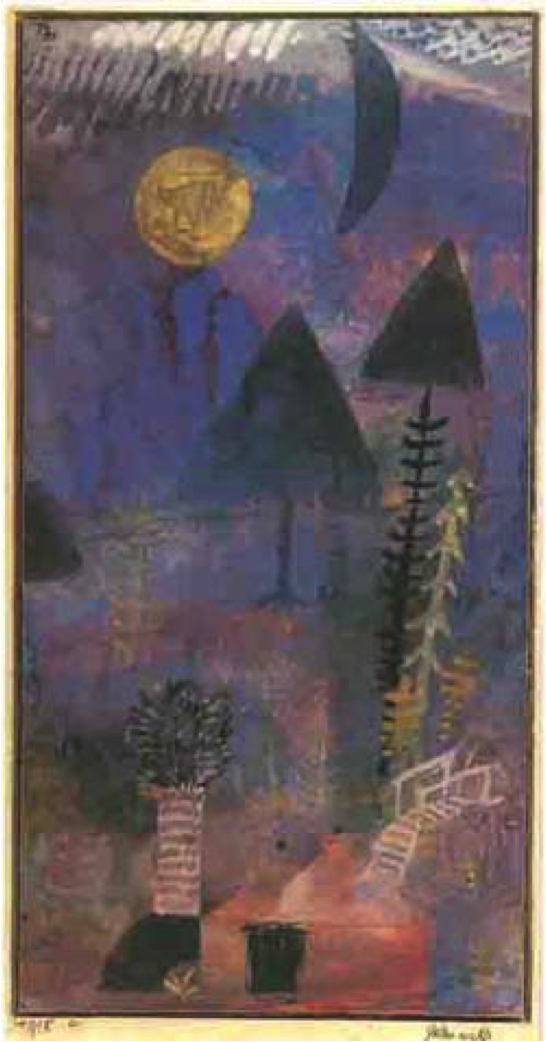

Garden at Night, Moon- and Shadow-Mushrooms,

Paul Klee, German (1879-1940)

Watercolor, 1918

Collection of Ernst Beyeler, Basle

The Search

But then the moon comes

up after all and with a glow bright

enough to wake you through

the bedroom curtains,

the night outside,

room beside which indoor rooms seem to

belong to a preliminary, rudimentary

dimension

and her there shining—

mother daughter friend anima mundi—

so still and low it's almost as though

you hadn't broken every vow you ever

made in the wayside tabernacles of

the night behind the forehead.

Go back to bed,

resolved this time to get all the way

to the other side of the dark, find

a place to set up shop, work without

letup by the light love supplies, rid

at last of mental fuss.

Soon you're

walking down a deserted road through

a nighttime countryside, wondering

if one of the locals is acquainted with

the lesser-known lunar writings.

Houses

are few, everyone's asleep,

the air suffused with a beautiful half-light

whose source you can't place. You're

strangely unafraid and in no hurry.

Included in Best Spiritual Writing 2012

The Algonquin Hotel

Times Square, New York

Tale á la Hoffman

Paul Klee, German 1879-1940

Watercolor, pencil and transferred printing ink on paper, 1921

Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Berggruen Klee Collection

Songwriting at the Algonquin

The night Kenneth Koch and I had dinner with Leonard

Cohen at the Algonquin, Leonard seemed less a famous

songwriter than a disconsolate figure from one of his songs—

having just lost, he told us, the great love of his life; all his

own fault. Kenneth had met Leonard before either was anybody

one legendary summer on the island of Hydra; Leonard still

with Marianne, Kenneth with Janice; whereas by the night at

the Algonquin, “So Long Marianne” was a classic; Kenneth

had written his magical second “Circus”—the first of his

poems to tie the paradise of writing to having and losing

Janice—and he and I lived up by Columbia together.

We felt so sorry for Leonard that the talk at dinner kept

circling back to love and loss, and as we philosophized and sympathized, traded stories and poured wine, the idea arose

that the three of us could compose the greatest love song of all

time. A joke, of course, except Leonard wasn’t kidding. He’d

write the music and split three ways the credit and the money—

and what with him staying right there at the Algonquin

up we went to his room after dinner to nail down

the song. Leonard offered hints; I jotted something down,

but Kenneth who’d glimpsed the comic implications, started joking

around about our pending musical celebrity and got us laughing so

hilariously at the sagas we devised for the lovers in the song

that in parting that night, we left for another time the miraculous

lyrics that would lift the world’s spirits—or break its heart.

In fact, decades went by and Kenneth had died before

I saw Leonard in person again—and then from a distant

row of an audience of eighteen thousand or so, at his late-life

concert at Barclays Center. Pretty crass venue; ads circling

and flashing, sound system blasting; I was about to walk out,

then—there he was—singing, miles away on the tiny stage, but

an almost apparitional officiant in the giant close-up monitor;

same grace and humor I remembered; at times, a supplicant

on his knees; the female backup singers like a plural

higher being, singing: If it be your will / to let me sing. . . .

Kenneth would have found the scene wonderfully

funny and intriguing, perhaps warranting ottava rima, as

the softest of hums filled the arena, everywhere and nowhere

like a high-tech trick—but no, the whole place was singing

along under its breath. Every heart / To love will come /

But like a refugee. The songs came and went on the spellbound

lips, as if bridging the rift central to the singer’s surreptitious

metaphysics with the bit of infinitude that sifts back to us by dint

of it; the voice at once of the lovelorn divine and bereft exiles

fleeing, in hopes of finding, one another. Or so it seemed

as the crowd dispersed in the night rain outside

Barclays Center. At the time of our dinner, I sang

my kids to sleep at night with “That’s No Way to Say

Goodbye,” whereas Kenneth sang Italian opera as we made

the toast and coffee—Di quell’amor, quell'amor chè palpito /

Dell’universo, dell’universo intero— before heading to our desks

to resume the endless quest: Kenneth to the exuberant

tat tat of his Olivetti, x-ing out and re-emending the poem

he would read to me that evening. “To Marina,” say, his

multi-temporal meditation on how what’s over is never over

even as it’s always forever gone: Is it snow, Marina, / Is it

snow or light? / Let’s take a walk. The gist of many

a Cohen line—Did I ever leave you? / Was I ever able? /

Are we still leaning / Across the old table? The lemon and

almond trees blossom and wither in lyrics set on the island of

Hydra, addressed to the woman to whom he’d said, So long

in that first hit song—the one he’d write to just before she

died: I’m so close behind, your hand could reach mine.

Left unmentioned at dinner at the Algonquin that

evening, as we pondered the enigmas of love and loss,

was that things between Kenneth and me had already begun

to go wrong; we were ineluctably entering a Leonard

Cohen song. Not a song that he’d already written or would

someday write, but one that might have pierced

the mystery to its heart, had we written it that night.

The Manhattan Review

Fall/Winter 2019-2020